Are you planning to start your university admission process? Whether you are going to college or directly to work, narrowing down your interests, capabilities, and preferences early can help counselors and students chart a plan through high school that will support their post-secondary goals.

A career counselor, does more than ask a student what he or she wants to do it. Several questions and tests can provide insights into goals, careers and jobs that will suit each student’s abilities, dreams, and requirements to initiate the university admission process.

Before you meet your counselor, I need you to identify a few points mentioned below before you start your university admission process.

- Which is/are your Favorite Classes?

- Consider Extracurriculars and Hobbies

- Explore Study Habits and Social Skills

- Know about your parents’ Income and Financial Preferences

- What is your career plan?

How Should I Begin College Planning with My Guidance Counselor?

Your initial conversations concerning college planning will focus primarily on your interests and strengths. Your guidance counselor might help you to think about these qualities concerning careers and paths through secondary education.

You should also discuss your goals with your guidance counselor. Suppose you are a student with a specific dream school or firm professional ambitions. In that case, your guidance counselor can help to point you toward the resources most appropriate for your goals. Suppose you still need to define your goals beyond high school. In that case, your guidance counselor can help to determine these for you through conversations, personality tests, or even interest inventories.

University admission process by IBO

The International Baccalaureate (I.B.) and the Diploma Program (D.P.), in particular, enjoy a high level of respect and recognition among the world’s higher education institutions. For students, success in the IB often results in advanced standing, course credit, scholarships, and other admissions-related benefits at universities.

The IB works with the higher education community to ensure I.B. Students get the recognition they have earned, as well as to examine and further develop our program to make sure we continue to offer the best preparation for university studies and life beyond.

Myth Busters

Olympiads are only/ sometimes necessary.

MIT, Harvard, and Stanford are free if you are accepted-True.

SAT is only/ sometimes required-Yes!

Like: Bradley, Bates, Bowdoin, or Clark University

Visa Requirements: USA

F-1 Visa, Admission Requirements

- A valid passport.

- A copy of the photo you will use for your visa.

- Printed copies of your DS-160 and I-901 SEVIS payment confirmations.

- I-20 form.

- School transcript and official test scores cited on your university application.

- Diploma (if applicable)

- Bank statements or other proof of finances.

The U.K.

You can apply for a student visa to study in the U.K. if you’re 16 or over and you:

- Have been offered a place on a course by a licensed student sponsor.

- Have enough money to support yourself and pay for your course – the amount will vary depending on your circumstances.

- Can speak, read, write, and understand English.

Europe Student Visa Requirements:

- Visa application form for a selected country.

- Proof of meeting the age requirement of the country.

- Valid passport.

- Valid documentation from a European university.

- Documents and evidence of adequate finances to meet your expenses.

- Flight tickets.

- Proof of meeting the language requirement.

General visa: Student Japan

- One visa application form (nationals of Russia, CIS countries, or Georgia need to

- submit two visa application forms)

- One photograph (citizens of Russia, CIS countries, or Georgia need to submit two photographs)

- Certificate of Eligibility (Note) – the original and one copy.

Hongkong

Documents to be submitted by the applicant:

- Application for Entry for Study in Hong Kong (ID995A)

- Your recent photograph (affixed on page 2 of the application form I.D. 995A)

- Photocopy of your valid travel document.

- Photocopy of your Hong Kong identity card (if any)

- A letter of acceptance from the educational institution.

South Korea

Required Documents

- Application form (for visa)

- Passport, and one copy of the passport I.D. page (the page with your photo)

- Passport-sized photo (3.5cm×4.5cm with white background; must be taken within the past 6 months)

- Certificate of Admission (issued by the International Education Team at Korea University)

What documents do I need for a Student Visa for the UAE?

- Your passport, along with copies of your passport.

- Few passport-sized pictures.

- The letter of acceptance into the UAE university or college.

- Proof of financial solvency to cover your tuition fees and living expenses.

Questions to Get the Conversation Rolling for college admission process

If you’re preparing to meet with your guidance counselor about college planning, here are some questions that you might consider yourself and then discuss with your guidance counselor if you see fit:

- What classes, do I need to take to be ready for college?

- What course track should I follow if I want to get into a school like _____?

- Which would electives best suit my interests or be most valuable to me?

- Should I take A.P. Classes? When and which ones?

- What schedule do you recommend for standardized testing?

- Does the school have college planning sessions?

- Are there any college fairs scheduled here or at nearby schools?

- Do you know of any alums who attend or have attended ______?

- Are there any scholarships I’m eligible for based on my skills and accomplishments?

- How can I begin to plan for a future career?

- Can I preview my transcript?

- Am I on track to qualify for the honor society? What requirements will I need to meet?

- What should I do it at home or over the summer to bolster my college applications?

- How do students from our school fair in college admissions? Do we have a particular reputation?

- Are there any other resources I should be aware of during my college search?

University admission process-The College Essay: Yogurt Edition!

The college essay is a lot like froyo. It comes in a variety of flavors. You get to customize it, and experimenting with new flavors yields blissful joy or, sometimes, yucky disappointment. When I applied to college many years ago (many years! I’m old. I wrote over a dozen unique essays to all the colleges I used to (btw – using 15 colleges – is not such a good idea. It is tiring. It costs a ridiculous amount of money in application fees, and counselors get mad at you for making them work so much! You have to narrow your list down after you get the acceptance letters anyway. I didn’t believe in the “one size fits all” approach when it came to the college essay, so I strove to write a unique essay for the differing prompts that each college required.

Recipe one: Froyo is meant for experimenting. So, it is the same with the college essay. Ever walk into a shop with one of those glass cases with all the toppings laid out in a symphony of delicious colors? Sure, it’s safe to get strawberry (that’s what I always get. ), But why always get the same?

College admission officers read upwards of tens of thousands of application essays in one application cycle, so how is your essay going to be different than the myriad of other competing essays?

Too often, I notice students caught in a rut when they are writing college essays. Many feel that there always needs to be a “moral to the story,” and so inevitably, all essays end with some variant of these sentences:

1) “I felt that I grew a lot from the adversity present in this situation, and it really shaped who I am today,”

2) “Having spent all four years of high school doing this activity, I feel like it became an inseparable part of myself,”

3) “Having been through so many things and having all of the qualities described above, I feel like I’m ready to tackle whatever will come my way.”

I feel like the most beautiful college essays are the essays that don’t hand the reader its moral (or “point” – so to speak) explicitly on a silver platter. The most compelling essays are those that sufficiently paints the picture for the reader and then leave him on his own to reach his own conclusions. Just look at the Mona Lisa – did da Vinci write, in a golden font at the base of the painting, “Look at her enigmatic smile. It is beautiful!”?

“But-but-” you ask, “Aren’t we trying to answer a question? If we don’t conclude, how are they going knowing that I addressed the question?”

Throughout your years of schooling, the standard introduction-body-conclusion system is ingrained into your mind. You were trained to begin an essay with a well-defined introduction with a thesis sentence, proceed into the body with topic sentences for each paragraph, and close with a conclusion that restates the thesis. Works for a push essay – works for research papers – but the college essays.

Boring. Yes

– most college essays will ask you to address a topic (like the MIT main essay)

– but approach it differently than you would with a research paper. A research paper is structured thus because you’re trying to provide a well-organized collection of facts to a reader that may or may not be interested in what you have to say. With the college essay – you’re trying to convey a slice of your life. Thus, you can take liberties in straying away from the conventional structure.

Experiment with your writing style. Approach it differently from how you would typically start an essay. Write it – and then come back at the end and ask yourself, “did I convey my point effectively?” If the answer is a resounding “yes!” – congrats!

“But- how do you do that?”

Recipe 2: Marshmallow-butterscotch-blueberry-Oreo-mango-pineapple-waffle? Not cute. Consider the following examples:

“At times, it appeared that we were surmounting an impassable obstacle. However, through the camaraderie and the solidarity of our aquatics team, we triumphed over our defeats and inevitably reached the pennant of victory.”

“Back in July, my friends made fun of me when I told them that I was going to start a swimming team. Laughing, they told me to return to my math problems. Today, standing in the limelight, I look over at my teammates and cannot help but marvel at how far we’ve come.”

Two sentences – notice a difference? Which one draws you closer to the author?

It’s not surprising that you may find the second sentence to be a lot more “down-to-earth.” The simple reason is that the sentence conveys a narrative in an everyday tone rather than adopting pedantic verbiage.

Another problem that I see a lot of my peers back in the day was when we were all applying to college. People would try hard to make themselves sound “educated” by using all of this advanced vocabulary in their essays. Not satisfied with “improved?” Try “ameliorated.” “Common” sounds too simple. What about “pedestrians?”

Their essays often turn into a convoluted amalgam of abstruse discourse, confounding the audience in a bold embellishment of protracted circumlocution.

A note of caution here: I am not trying to say that you should tone down your writing if you use a lot of vocabulary – but be careful of what the “voice” in your essay sounds like. Does it sound like you, or does it sound like someone that is trying too hard with a thesaurus? At the bottom line, the essay should be about you – so don’t be afraid of showing your own voice! (Believe me – an essay that “tries too hard” is straightforward to spot)

(I’m going to segue into something cool that you can do with your essay here. Please don’t solely use this test to measure how “good” your essay is! That is something no machine can tell you. You have been warned!)

Recipe 3: The first and last spoonful is the sweetest.

Sometimes I steal a bite of my friends’ froyo (instead of buying my own) coz I think one spoonful with all the icy yoghurt-tangy goodness is heaven enough.

And so, it is with the college essay for your university admission process.

Consider your lead-in and your ending (namely, the first sentence and your last sentence, but more broadly, your first paragraph and your last paragraph).

When you took the SAT, you were probably encouraged to use an engaging opening sentence in your essay since the graders will spend no more than a couple of minutes on your essay, and sometimes the opening sentence is the most essential factor in “luring” the reader in. The college essay is very much the same – the admission committee has thousands of them to sort through, and a bland essay would probably begin with something like “An experience that changed my life is…” “Someone that I looked up to is..because…”

Be engaging, be active. Paint a picture for your audience.

Personally, I liked telling stories in my essays. I always began each essay with a short narrative since it makes the “lead-in” a lot easier (you can basically, segue into whatever you want to talk about through the little story that you’ve laid out).

In conclusion, my A.P. Literature teacher was fond of saying that a great essay always contains something at the end for the reader to think about. For example, classics in world literature rarely resolve their conflicts and plot in a single, sweeping chapter that encompasses everything that you possibly would like to know about each and every character afterwards. Usually, classics end in such a way that gives you pause after reading the last sentence of the previous paragraph and lets you consider the implications of the hundreds of pages that you have just read before.

What does this mean? No “happily ever after” endings, no trite endings like “joining the aquatics team had truly made me a new person.” Good things to consider, though, are: offering the reader something to think about (it doesn’t have to be in the form of a direct question) or a tie back to your beginning narrative (the second part of the story in your intro, for example – I tend to utilize this pretty often – drawing the reader back to the scene I painted in the beginning). Avoid unnecessary puns or wordplay, moralizing statements (“I have truly discovered the meaning of courage”), and lame witty comments at all costs, although for some odd reason, I’ve read dozens and dozens of SAT essays that end like this (through grading the exams for the SAT Prep program I direct).

Recipe 4: Making great yoghurt takes time.

Do you know that frozen yoghurt melts and freezes much slower than ice cream because yoghurt has a higher heat of fusion than milk? (!!! I was amazed when I discovered this)

Take your time when you draft your essay for your college admission process, to begin with. Your essay should never be churned out hours before the deadline in a desperate struggle to complete your application (although I was guilty of that for one essay). A well-written essay takes time to distil in the back of your mind and can’t be “forced out” by hours of sitting in front of Microsoft Word.

Something I like to do when I have to write an essay I’ll actually Scotch-tape the prompt on top of my desk as soon as it’s assigned and leave it there until I begin drafting my essay. I also try to remember the gist of the prompt and think about possible approaches and content during the “down-time” of my day (waiting for the bus, being bored in lectures, shopping at the supermarket etc.). Note that this kind of “thinking” isn’t like the “okay-I’m-going-to-sit-down-now-and-only-think-about-the-essay” sort of thinking, but rather an ongoing process in the back of your mind.

If you get used to thinking like this, you automatically begin to process things in your mind all the time without meaning to do them. For example, my lead to the Stanford essay came when I was showering; Caltech when I was walking to a convenience store. Now, I have a particularly pestering pest question that eludes my attempts at trying to rationalize it. In that case, I’ll store it in that. “thinking” compartment in the back of my brain, and chances are I’ll discover a new lead to doing the problem at some random time during the day.

This is why a good essay takes time. Just like making good yoghurt takes time for all the bacteria to happily multiply in warm milk. A “brute-forced” essay, like its counterpart in mathematical proofs, should be the last resort simply because it has no elegance. Therefore, if you still need to start thinking about your Regular Action essays, start now! You will thank yourself later 🙂

Recipe 5: One word – Passion.

When writing college essays, it really boils down to one word. Passion. The essay should almost be “an extension of yourself – what you like to do, your dreams, and what defined you as a person through high school.” Speak to the audience. Paint a picture in words. Share with them what you loved in high school, your difficulties – what defines your life. I look at the college essay, and it is the only expressive part of the application that you get (well, aside from the interview). It’s the only opportunity where you could share a slice of your life away from mundane test scores, GPA, and lists of activities with your readers. Why not capitalize on this opportunity and try hard to present who you are?

Write from your heart – better yet, write with the energy and drive that is uniquely yours (I would write, “write with your soul,” but I thought that sounded too cheesy. )

FAQ: University admission process that doesn’t really fit anywhere else!

Should I get my teachers/friends to proofread the essay?

For my very first college essay, I asked two teachers to revise it for me since it was “omg-this-is-my-first-essay!” Although I was grateful for the work of my teachers, my essay turned into 13 rewrites and a final product that sounded nearly nothing like me. After submitting that essay for my Early Decision school, I quickly trashed it and proceeded to write the ensuing Regular Actions entirely from scratch. Upon finishing an essay, I usually proofread the completed essay 10 times over three days or so (you shouldn’t proofread the essay all in one sitting since your tired brain probably will be fried, and you will end up skimming through the same mistakes). And that is it!

Thus, It is all up to you. Try asking an adult to read it and see what they feel, although I do not believe you must have had an adult read it to make it a good essay. At times, you risk losing your original voice from over-editing.

What about the essay prompts?

I addressed the explanations above, generally to the prompt of “tell us about an experience that shaped who you are” or one of MIT’s essay prompts (“Tell us about the world that you came from.”). However, one important thing is to pay attention to the prompts of your college essays. Some colleges are very complimentary, and you can pretty much attach anything you want (when I applied – Columbia and Harvard), while others are tailored, and you have to answer their questions (Stanford, Caltech). If they ask for a specific response, address the prompt! (This is also why I wrote so many different essays for each school).

Word count for your college essay?

This is the old argument that no one can really address, except for the admission committee who would be reading your essays. I would go with the aged wisdom of following the instructions on the application essay. If they specifically ask you not to overdo it (like MIT), keep it around 500 words seem reasonable. If they do not specify a word limit, exercise your best judgment. Chances are that you should always be able to slim down your essay. If it’s tough determining how much fluff you have in your essay, go through the entire essay sentence by sentence and ask yourself, “what is the connection of this sentence to the rest of the essay? Do I really need it?”

Can you post your essay?

In short, no. Be creative! I wonder why people need sample essays while applying to college since the application essay should be entirely and initially yours. How can you tailor someone’s dreams and writing styles to your voice?

Great, links? Other questions?

I thought that the College Board’s guide to writing a good essay was well-written. Something else that I should have mentioned above, but College Board does, is this! Do not Write a Resume. Only include information that is found elsewhere in the application. Your essay will sound like an autobiography, travelogue, or laundry list. Yawn.

Also, Feel free to leave a message if you have other questions about the essay.

Finally, what does this entry have to do with froyo?

Nothing really. I wanted to write a blog on how to write the essay, but I had to use froyo to lure you in (if you’re still reading this very, very lengthy blog at this point). I’ll leave you with some visual icy goodness to compensate.

QUOTE:

- Never use a metaphor, simile, or another figure of speech that you are used to seeing in print.

- Only use a short word where a short one will do.

- If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

- Never use the passive when you can use the active.

- Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

- Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous. -Excerpt from George Orwell, “Politics and the English Language,” 1946.

So once upon a time, I wrote a blog comparing the college essay to froyo. Since then, the application was revised, and although I still believe in the merits of the first blog concerning an extended college admission essay (500-1000 words), it definitely doesn’t apply entirely to the new short-answer system that MIT adopted.

A few months ago, I created a bogus account on my.mit.edu, so I could actually catch a glimpse at what the new application looks like (it really doesn’t look that different, ha), and I’ve been thinking about how I would approach these essays. Although nothing here is the product of intense cognitive, I thought I’d share some of my views on these small essays. Essentially, you have 5 “mini-essays” – What You Do for Pleasure (“pleasure.” – 100 words), Department at MIT (“department” – 100 words), What You Do That’s Creative (“creativity” – 250 words), World You Come From (“world” – 250 words), Significant Challenge (“Challenge” – 250 words), and that’s it! Less than 1000 words total.

Easiest things first – the “Pleasure” and the “Department.” prompts are not really “essays,” but short answers, so they can be quickly answered. My advice is to go ahead and be honest with them (well, you should be honest in your entire application ), especially with the “Pleasure” essay. The admission officers (“admission committee”) are not looking for “standard” answers, and you won’t get brownie points by putting down “programming,” “building robots,” or other “MIT-y.” answers (although they also definitely won’t penalize you if they do happen to be things that you do for fun). Just be honest!

Many people stress out about the “Department” essay, but I can tell you that MIT DOES NOT admit on a quota, and you WILL NOT be penalized by which department you put down on that blank (I don’t know how many emails I’ve got on this subject already – seriously, the admission committee are not lying at you, and no – there is no conspiracy, either). Therefore, you will not seem more impressive if you put down Philosophy over Mechanical Engineering. When I applied, I put down Chemical Engineering (oh, such were the days of my innocent youth when I believed that Chemistry was trivial), but now I’m happily a Biology (and pending History) major. Your interests may shift after you enrol at MIT (and realize how brutal some of the courses here can be), and that’s perfectly fine! So do not worry too much about your university admission process.

For the “Creativity” essay, I would encourage you to look at the connotation of “creativity” from a new angle (in a sense, be creative about exploring creativity :P). You can go broader than physical things like creative projects or creative inventions. I would investigate writing about creative ideas, creative ways of looking at things, and creative ways of solving problems. I wrote about a concrete research project I did when I applied. Still, I thought that was quite boring in comparison to the other things that I could have written about, so I encourage you to explore this topic further. 🙂 Ah – OK, now we come to the challenging 250-word essays.

So back in the day, we had a choice between these two essays to write a long essay on, but now they’re requiring you to write about both of them, but as shorter essays. I really enjoyed the “world” essay – and I thought it was one of the best prompts out of the prompts for the 15 colleges that I applied to (number one was still Stanford’s “photograph” prompt – I loved it. Sorry, MIT).

The Challenge now is how to condense all the things you want to convey in mere 250 words. For me to see what a 250-word word limit is really like, I wrote a 250-word essay. Not on MIT’s prompts, though. He held up the sheet of wrinkled paper, his eyes in silent protest. The tattered bill requested 13,800 dollars for a three-day hospital stay. “Why call the ambulance? Just leave me alone!” the frail old man muttered. Just a week ago, Mr. Vu suffered a stroke that required hospitalization. Because he could not understand English, Mr. Vu had not applied for health insurance, resulting in an outrageous bill.

An internship at an Asian clinic opened my eyes to the untold story of limited-English proficiency patients, who often struggle to obtain health care in a maze of foreign forms and convoluted policies. Suffering from a worsening stomachache, Mrs. Wong was neglected in the county hospital for over two hours, unable to flag down a passing nurse for assistance because of the language barrier. Clutching an X-Ray order, Mr. Park searched in vain for Radiology in a blinding flurry of English letters.

Over the summer, these stories became too familiar – accounts of immigrants fighting for their right to care in a shockingly monolingual health system. After the internship, I participated in a medical interpretation training program. I was licensed as a Mandarin health interpreter in November. I wanted to change the status quo. My experiences this summer solidified my conviction of entering public health, especially immigrant health, as my future course of study. America has long prided itself as a “melting pot” of cultures. Isn’t it only fitting that there exists equitable access to health care, regardless of the language spoken?

The word limit is short.

Now, a disclaimer: I want to say that this is not intended to be a “model essay” (I think the ending can use some more work, among other things), but I thought this would be easier in illustrating a point. If you look at the essay, I like going narrative -> point -> how it connects to me. In fact, this is what I use for most of my essays. Here is the same essay deliberately made worse (but to illustrate a widespread problem in college application essays.

Last summer, I worked in an Asian clinic in Oakland, California. Throughout the summer, I realized the plight of immigrants when it came to obtaining equitable health care. In the modern health industry, immigrants and other residents with limited English proficiency are often overlooked because they are unable to communicate their symptoms to the doctor and complete paperwork in English. This problem is exacerbated when they cannot apply for health insurance, resulting in excessive health bills. This kind of neglect is no longer acceptable in a country that claims to be the “melting pot” of cultures.

Many patients suffer extended waits in the hospital, unable to obtain assistance. A worsening stomachache may be an initial sign of appendicitis, which needs to be treated expeditiously. Hospital signs are often not translated into other languages, making navigation difficult for elderly patients. These scenes are played across hospitals in the nation every day.

After my experiences this summer, I realized that I wanted to channel my energy into revitalizing this system. It is no longer sufficient for us to stand on the sidelines and watch. To this end, I participated in a medical interpretation training program and was licensed as a Mandarin health interpreter. I hope to contribute my efforts to the field of public health, especially immigrant health, in the future. These patients cannot afford to passively wait for language-accessible care and continue to sacrifice their right to treatment.

Also 250 words, but this essay is riddled with problems, many of which Orwell pointed out in the blurb above.

- The essay is filled with extraneous and needlessly complicated words. (“I wanted to channel my energy into the revitalization of this system”)

- The essay lacks a personal voice – it is very passive (“These scenes are played,” “immigrants are often overlooked,” “the problem is exacerbated”)

- The essay never “shows” – it only “tells.” Show don’t tell!

I cannot emphasize this enough. This essay points out the many problems of the healthcare system, but does not offer any examples of the issues. At the end of the day, which essay will readers remember better? An essay that speaks in general terms or Mr. Vu with his bill?

Personally, After MIT switched from extended essays to short essays, this point is even more pertinent. You can’t afford to waste words, speaking in vague terms that do not convey the meaning.

When the admission committee reads thousands of essays on end, you need to stand out. Ideally, your essay should pack enough punch (that is a cliche :P) so that your readers have a “take-home message” (another cliche :P). But you need something memorable about your essay. If you feel bored writing your essay, the person reading your essay will be bored too. Make it vivid – let your story shine.

Finally, the other point I want to convey: Trim the extra fat!

I narrowed down the first essay from over 400 words to just 250. Chances are, you can do the same too. The second essay is plagued with extraneous words. Actually, it can be narrowed down to just this without loss of meaning:

Last summer, I worked in an Asian clinic, where I realized the struggle of immigrants to obtain equitable health care because of the language barrier. They often cannot apply for health insurance, resulting in excessive bills. This is not acceptable in America, which claims to be a “melting pot.”of cultures. Many patients suffer extended waits in the hospital, unable to get help.

A worsening stomachache can lead to appendicitis that requires rapid treatment. Signs are often written in English, making navigation difficult for elderly patients. It is no longer sufficient for me to stand on the sidelines – I want to make a difference. To this end, I participated in a medical interpretation training program and was licensed in Mandarin. I plan to work in the public health field, especially in immigrant health. These patients cannot afford to passively wait for language-accessible care and continue to sacrifice their right to treatment.

This new essay is only 154 words. Although it sounds stilted and should not be submitted as a complete essay, it still shows how much excess fat one can usually trim from a typical essay. Not to reiterate too much from the previous blog that I wrote, the influential essay, IMO, is the one that really shows who you are, where you’re coming from, and what your loves are – in your own voice. Both the “world.” and the “challenges” essays are structured so that it is focused on you and your stories. Use these opportunities to tell a story – to convey who you are. There’s no need to repackage your tale in fancy rhetoric or educated vocabulary. Just as we see in world literature: often the best stories are, really, the simplest stories.

What are they looking for in the college application essay? That is the wrong question.

There is no magic formula. The application essay is the first published piece of writing for almost all young writers. It goes out into a world of unknown readers who hope to learn something tangible from it. Unlike the audience of teachers provided by the school—who are paid to like you, or at least pretend as if they do, no matter what you fumble out about Hamlet or the Ottoman Empire—the admissions officers who read your essay have no stake whatever in your success.

This piece is also a specific literary form, like an epic or a limerick, and has its own clichés to be avoided, some of which follow. (NB: everything I say you cannot do, you can do. You must be careful with advice about cure-alls. The Trip: “I had to adjust to very different foods, customs, even daily schedules, in my visit to Europe/Israel/Cleveland/fill in the blank. …” Everything in Trip essays is different, except the essay itself, just like all other Trip essays.

Miss America: This essay—”I think world peace is the most important issue facing us today….”—offers simpleminded solutions for complex problems that you don’t know the first thing about from personal experience. “Writing,” said E. B. White, “is an act of faith, not a trick of grammar.” It’s not any trick, in fact. At its best, it’s just you. The Perspirant: In response to the essay prompt to discuss “a challenge you’ve faced,” student anxiety often leads to “This essay is the greatest challenge I have ever faced .” Don’t write about the application process (admissions officers sometimes call such applicants “sweaty”).

The Jock: “Through wrestling, I have learned discipline, determination, and how to work with people… .” Written by many types of students, not just neckless mouth-breathers, this isn’t subject, but a formula: Through X, I have learned Noble Value A, High Platitude B, and Great Lesson C. (You know you’ve written this essay if you can substitute “hard work,” “cooking meals at the soup kitchen,” or “my career as a mugger” for “WRESTLING,” and it still makes sense.) In essays and in life, attempts to force people into choosing what to think of you don’t work. You have to be yourself; they decide what to think.

Pet Death: “As I watched Button’s life ebb away in the street, I realized all the important things I value in this world… .” If you have pets, keep them alive as long as possible. If they die, dig a hole, have a lovely ceremony, and then keep quiet about it. (Incidentally, E. B. White wrote one of the great essays of this century, “Death of Pig,” defying everything I am saying in brilliant detail. Try it if you dare.)

My Favorite Things: “Here are a few things I am in: abandoned puppies, moonbeams, fudge brownies. Things I am against acne, mean people, nuclear holocaust… .” Writers of MFT are called “fluffballs” in admissions parlance—need I say more?

Tales of My Success: “But finally, when I crossed the finish line and received the congratulations of my teammates, I realized all the hard work had been worth it.” Imagine how often that gets written, and then spare the admissions staffers one more variation on the theme. Let others—teachers and counselors—talk about your successes instead.

My Memoirs: Don’t try to stuff eighteen years into 500 words. It is not that an autobiography cannot be done in this space; it’s just profoundly tricky. Write about something more petite.

Now, what you should do?

The secrets of the application essay are few and not so secret:

Write to discover something. If you already know what you want to say, the reader is already sleeping. Invite the reader along, don’t push them around. Read other essays. Familiarity breeds knowledge. Practice. The piece you send to colleges shouldn’t be the first personal essay you’ve ever worked on.

Tell a story. Give the details.

Find a style that is just informal enough. It’s not an essay for history class. Think hard, and write. If you think of something funny, write it down. If not, don’t. Write something only you could write.

The college essay is often the most challenging part of an application for Admission to a college. We’ve put together the following tips and hints to help you get off to a good start. These are comments from our admissions staff, who read your essays and evaluate them in the admission process. We can’t guarantee results, but this advice might help you get started.

Top 15 Essay Tips from The Readers

View it as an opportunity. The essay is one of the few things you’ve complete control over in the application process, especially by the time you are in your senior year. You have earned most of your grades; you’ve made most of your impressions on teachers; and chances are, you’ve already found a set of activities you’re interested in continuing. So, when you write the essay, view it as more than just a page to fill up with writing. View it as a chance to tell the admissions committee about who you are as a person.

Be yourself. If you are funny, draft a funny essay; if you are serious, write a serious one. Refrain from reinventing yourself with the essay. Make it fun. Suppose you are recounting an amusing and light-hearted anecdote from your childhood. In that case, it doesn’t have to read like a Congressional Act — make it fun!

Tell us something different from what we will read on your extracurricular activities or transcript list. Take the time to go beyond the obvious. Think about what most students might write in response to the question and then try something different.

Don’t try to take on too much. Focus on one “most influential person,” one event, or one activity. Tackling too much tends to make your essay too watered down or disjointed. Concentrate on topics of true significance to you. Do not be afraid to reveal yourself in your writing. We want to know who you are and how you think. Write thoughtfully and from your heart. It’ll be clear who believes in what they are saying versus those simply saying what they think we want to hear.

Essays should have a thesis that is clear to you and to the reader. Your thesis should indicate where you are going and what you’re trying to communicate from the outset.

Do not do a history report. Some background knowledge is OK, but do not re-hash what other authors have already said or written. Answer each school’s essay individually. Recycled “utility essays” come across as impersonal and sanitized. The one exception is an essay written for and submitted to Common Application member schools.

Proofread, proofread, proofread. Nothing says “last-minute essay” like an “are” instead of “our” or a “their” instead of “they’re.”

Keep it short and to the point.

Limit the number of people from whom you request feedback on your essay. More input creates an essay that sounds like it has been written by a committee or results in writing that is absent of your voice.

Appearances count. Formatting and presentation cannot replace substance, but they can certainly enhance the value of an already well-written essay.

Many things in life – but specifically the college application process – are easier for people who have a powerful sense of self and know exactly what they want. Unfortunately, there are very few people – especially 17-year-olds facing the college application process – who have an extreme sense of self and know exactly what they want.

Now, I actually think this “indecisiveness” is a good thing. It means you are flexible and well-rounded and would do well in many settings, which is incredible. Unfortunately, applying to college makes this a complex trait to live with. When you begin looking at schools, for example, people ask you if you want big or small like it’s something you should inherently know, as if you’ve learned how big you want your college class sizes to be as long as you’ve known your eye color.

When you leave a campus tour, your parents ask you if you could “see yourself” on that campus. “Of course, I can,” I used to tell my mom. “I was just there.” And when you look at supplemental essay questions, you’re asked, “What makes you happy?” and “What are your dreams?” as if you only have one thing that makes you happy or one dream for the future, and you should be pumped that someone has finally asked you about it!

My point is: essay topics are going to come slowly to you if you know exactly who you are and what you want. And that is OK because I can help. Here are five steps to finding the perfect supplemental essay topic. All it requires is a piece of paper, a pen, and some reflection:

Write down five things you’ve learned in the last few years that you found fascinating. These could be things you learned in a history class, your favorite novel, or a podcast you listen to on your walk to school. They could even be topics you need to learn more about but want to explore further.

Write down five adjectives your friends would use to describe you. Think about your role in your group of friends and what words they would use to tell you if asked. Write down the five times in the last few years when you’ve been your happiest. Think of those moments when you cried laughing, perfectly felt content, or were in fantastic company. Write down where they occurred and why they made you so happy.

Write down five things you’re excited to tackle in college. Have you considered joining a climate action group in college and saving the environment? Do you get butterflies in your stomach when you think about studying abroad in Chile? Are you excited to push yourself out of your comfort zone with art classes or intramural sports?

Take a highlighter to your lists. Highlight the items that feel the most important to you. Which things made you smile as you wrote them? Which ones felt like “aha!” moments where a piece of your identity or priorities clicked for you? These highlighted items should create a little narrative of you; they should indicate essential themes that should definitely be present in your essays. If a few things you wrote highlight your penchant for social activism – poof! You’ve found a topic for one of your essays.

Pull examples from these lists – a class project you found intellectually exciting, a trait your friends would use to describe you – and allow them to be present in your essays because you’ve identified them as necessary. And focus on item #2 on this list because these adjectives should also inform how you write your essays. If your friends would describe you as “sarcastic,” a hint of sarcasm should be present in one of your essays. Make sense?

Turns out a blank piece of paper and a pen can really clarify this process, even for those of you out there who can’t choose a restaurant, let alone an essay topic for the question: “What are your dreams?”

University admission process: When to start?

Freshman Year

Faced with more challenging high school classwork, you’ll need to pay attention to what your new teachers expect from you and look for ways to work harder and smarter. Grades are essential in ninth grade, but seek balance so that you are challenged without being overwhelmed. Don’t be afraid to ask for help if you need it.

Get involved. High school is not a four-year audition for college, but rather a time to develop yourself. Beyond grades, social connections and extracurriculars are important. Use part-time jobs, community service, arts and music, robotics clubs, and other activities to engage with others. Read voraciously. Dive into books, newspapers, magazines, and blogs. Explore subjects that engage you. Additionally, check out TED Talks, YouTube videos, and free online courses.

Find mentors. Look for knowledgeable people who can offer helpful advice: teachers, coaches, counselors, and friends. These relationships can pay off in other ways, too. People like to help students they know.

Schedule downtime. That means turning off electronic devices. No phones. No screens. We all need time to daydream and think about ourselves and our place in the world. Identify ways to relieve stress. For high school and college, you’ll need a sustainable model for sustainable success, including finding healthy ways to manage stress and getting enough rest.

Sophomore Year

Focus on better understanding your strengths and interests – and how to develop them. Challenge yourself wisely. Strive for solid grades and take on new challenges inside and outside the classroom. Ask for help if needed; avoid overtaxing yourself. Balance is the goal.

Speak up in class. Learning at the college level is about exchanging ideas between professors and peers. Critical thinking and the ability to articulate your thoughts and opinions are skills that contribute to college success. Sleep. The typical 15-year-old brain needs eight to 10 hours of sleep to function at 100%. Refine your route. Look ahead to 11th and 12th-grade courses of interest and plan on any prerequisites. Take advantage of rigorous courses that are in line with your academic path.

Learn from the masters. As you take inventory of your interests, find people who work in related areas. Listen to their stories. A 20-minute conversation with a professional could turn into a fruitful internship opportunity.

Create an activities list. Keep track of your hobbies, jobs, extracurriculars, and accomplishments. This will form the basis of your resume and will be essential in preparing for college interviews and applications and for jobs, internships, and summer programs.

Make your summer matter. Work, volunteer, play sports, travel, or take a class. Research summer programs and internships to move beyond the scope of your high school courses. Plunge into an activity that excites you. Settle a testing strategy and test-prep plan. Use your PSAT scores and other practice tests to help you identify the proper test for you, specifically the SAT vs. the ACT. Need a better test-taker? With so many colleges now test-optional, the tests are something you may want – but not need – to take.

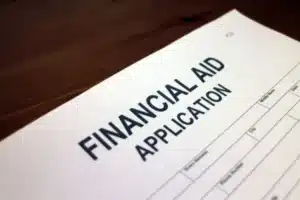

Consult your parents. Talk with them about expectations for college, including how much your family can pay. It’s much better to discuss costs at the start of the process.

Junior Year

Your grades, test scores, and activities this year form a large part of what colleges consider for Admission. Prepare for your exams, do your best in class, and stay active and involved. Plot out your calendar. Talk with your parents and school counselor about which exams to take and when. If your 10th-grade PSAT scores put you within reach of a National Merit Scholarship, concentrated prep time might be worth it. Then take the SAT or ACT. As many test-optional colleges will remain so, good scores can help but are optional. You can use A.P. exams to show intellectual rigor instead of, or in addition to, the ACT or SAT.

Immerse yourself in activities. It’s your turn: Junior year is the time to fully engage in and become a leader in extracurriculars you enjoy both in and out of school. These are opportunities to grow intellectually and socially and to show you are dedicated and play well with others.

Build your college list in the spring. Once you sense your grades and get your test scores, if any, talk to a school counselor and assemble a list of target, reach, and schools. Use tools to aid your research. Explore college websites and other resources such as StudentAid.gov, which is the U.S. Department of Education’s financial aid website, and the U.S. News My Fit Custom College Ranking tool. And clean up your Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and other social media accounts since admissions folks may check them out.

Visit, And connect digitally. You can check out a few campuses in person. If not, make use of COVID-improved college websites and webinars. Attend college fairs and information sessions. Grab the admission rep’s card and follow up via email with a thank-you note or questions whose answers still need to be made available on the college website.

Get recommendations. Right after spring break, ask two teachers with different perspectives on your performance if they will write letters for you. Choose teachers who will effectively communicate your academic and personal qualities.

Write. Reflect on your experiences and strengths as you prepare to write your college essay. Procrastination causes stress, so aim to have first drafts done by Labor Day of senior year. Please share them with an English teacher, parent, or counselor.

Senior Year

Colleges look at senior-year transcripts, so keep working hard in your classes. Finish testing. If necessary, you can retake the SAT or ACT in the early fall. Check the admissions testing policies of your prospective colleges. Are they test-optional or require you to submit SAT or ACT scores? It may be strategic to share scores with some schools but not others. Know your deadlines. Many colleges have multiple deadline options. Consider the implications of early action and early, rolling, or regular decision – and confirm the rules and deadlines for financial aid – so you can plan accordingly.

Apply. Craft your essays with a well-thought-out narrative. Fill out applications carefully. Review a copy of your transcript. Have you displayed an upward trend that should be discussed? Does an anomaly need context? Discuss any issues with your counselor. Leave yourself time to reread essays and clean up any errors.

Follow up. Check that your colleges have received recommendation letters, high school records, and SAT or ACT scores from the testing organization. A month after you apply, call the college, and confirm that your file is complete. Confirm aid rules. Check with each college for specific financial aid application requirements. Dates and forms may vary. You’re typically required to complete the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, known as the FAFSA, which needs some information from your parents.

Make a choice. Before committing to a college, try to visit or even revisit the schools where you’ve been accepted. Talk with alums and attend an accepted-student reception. Then make your college choice official by sending in your deposit.

How to Get a Great Letter of Recommendation?

Colleges often ask for two or three recommendation letters from people who know you well. These letters should be written by someone who can describe your skills, accomplishments, and personality. Colleges value recommendations because they:

Reveal things about you that grades and test scores can’t Provide personal opinions of your character Show who is willing to speak on your behalf Letters of recommendation work for you when they present you in the best possible light, showcasing your skills and abilities.

When to Ask for Recommendations

Make sure to give your references at least one month before your earliest deadline to complete and send your letters. The earlier you ask, the better. Many teachers like to write recommendations during the summer. If you apply under early decision or early action plans, you’ll definitely need to ask for recommendations by the start of your senior year or before.

Remember Some teachers will be writing whole stacks of letters, which takes time. Your teachers will do a better job on your note if they don’t have to rush.

Whom to Ask

It’s your job to find people to write letters of recommendation for you. Follow these steps to start the process:

Read each of your college applications carefully. Schools often ask for letters of recommendation from an academic teacher — sometimes in a specific subject — or a school counselor or both.

Ask a counselor, teachers, and your family who they think would make good references.

Choose one of your teachers from a junior year or a current teacher who has known you for a while. Colleges want a contemporary perspective on you, so a teacher from several years ago isn’t the best choice.

Consider asking a teacher who also knows you outside the classroom. For example, a teacher who directed you in a play or advised your debate club can make an excellent reference.

Consider other adults — such as an employer, a coach, or an adviser from an activity outside of school — who have a good understanding of you and your strengths. Most important, pick someone who will be enthusiastic about writing the letter for you.

If you need clarification about asking someone, politely ask if they feel comfortable recommending you. That is an excellent way to avoid weak letters.

How to Get the Best Recommendations?

Few teachers write many recommendation letters each year. Even if they know you well, it’s a good idea to take some time to speak with them. Make it easy for them to give positive, detailed information about your achievements and your potential by refreshing their memory.

Here is how:

- Talk to them about your class participation.

- Remind them of specific work or projects you are proud of.

- Tell them what you learned in class.

- Mention any challenges you overcame.

- Give them the information they need to provide specific examples of your work.

If you need a recommendation letter from a counselor or other school official.

Follow these guidelines:

Make an appointment ahead of time. Talk about your accomplishments, hobbies, and plans for college and the future.

If you need to discuss part of your transcript — low grades during your sophomore year, for example — do so. Explain why you had difficulty and discuss how you’ve changed and improved since then.

Whether approaching teachers, a counselor, or another reference, you may want to provide them with a resume that briefly outlines your activities, both in and outside the classroom, and your goals.

Final Tips

The following advice is easy to follow and can really pay off:

Waive your right to view recommendation letters on your application forms. Admission officers will trust them more if you haven’t seen them. Give your references addressed and stamped envelopes for each college that requested a recommendation.

Make sure your references know the deadlines for each college.

Follow up with your concerns a week or so before recommendations are due to make sure your letters have been sent.

Once you’ve decided which college to attend, write thank-you notes. Tell your references where you’re going and tell them how much you appreciate their support.

How do A-level grades matter? I mean percentages and the number of subjects matter. What is the relative weighing of SAT and A levels?

-A-level grades matter less than it seems. Still, your education record should show a minimum level of merit and consistency of results. There is no definite relative weighting for scores. The admission process is holistic, so everything is still being determined. Many times, high SAT scorers get rejected, and lower ones get accepted. Remember that you must pass a minimum level of about 600 in reading and 700 in Math.

Writing is not as critical as there are essays. But yes, your writing style in SAT should match the essays. In other words, you should write your own essays.

Apart from SAT, do I need TOEFL?

-Yes, you do. Although there are a few colleges that do not require a TOEFL score, most of them do require one. So, take it.

When they ask, “what defines you” what exactly are they asking for?? What defines you?

-Not much, just the things that define you. In other words, they want to know about the ‘real you,’ which can be smart, generous, weird, stupid, adventurous, and anything, but whatever you write must be authentic. Often, they look for the passion and determination for learning, but only write what a feature of yours is. They will look for evidence for the truthfulness of your claim. Interviews and other questions’ answers reflect your nature, so be honest. They are looking for honesty. You never know. 😉

Is it wrong to ask previous applicants for sample essays or ideas about essays?

-Nope, not wrong, but resist plagiarism (although I believe you won’t.just a precautionary measure). Often reading others’ essays preoccupy your mind with their ideas and writing styles, preventing you from showing up in the essays. Got my point, I hope.

What exactly do they look for in a person?

-There is no single requirement. For schools looking for diversity and multiple types of talent, there are no single criteria for picking students.

Which universities offer financial aid?

-You Check their individual websites and college board college search portal for this information. Look at their policy of providing aid. Need-blind (need doesn’t affect admission decision), need-based (your whole need will be met if you get the chance to admit). I am still determining other policies that exist. Someone else may want to help.

How to prepare for the SAT and TOEFL? Can I take these exams after my High School /A level?

-Different schools have different deadlines for when you can take your SATs/ TOEFL. Check the specific school’s website and go by it.

Usually, you must accept them by the December of your application cycle. If you are entering school in 2024, you must take them by December 2023.A Look at some preparatory books (Barron’s/ Princeton Review)

First. Look at some of the sample questions. Decide which sections you need help with. Read those sections from the book and practice! Practice is the most important thing for these standardized tests. So if you are applying after HSC (you have to take a gap year in that case, which is perfectly OK), you can take those tests after HSC. I’ll repeat, taking a gap year does not harm your Admission at all.

How should we seal our envelopes?

-Either get A4 size envelopes or envelopes for sending letters. Inside the envelope, put your documents. For a more organized method, please make a list of documents inside the envelope and attach it to all the papers using paper clips. The use of paper clips is appreciated to avoid wear and tear on the documents which will be scanned in the admission offices. You can make 3-4 envelopes for different purposes and put them in a larger envelope.

The envelope containing your school records, other letters from the guidance counselor, and transcripts should have the seal of your school and the guidance counselor’s signature after it is closed. I recommend that the envelope of other recommendation letters is also sealed and signed. On the final envelope, put your name, address, birth date, and the address and phone number of the recipient on the envelope clearly, and you are done.

I have never attended an international competition: Am I doomed to the elite U.S. Universities?

-This question came up because there was a rumor that you need international exposure to get into elite U.S. universities. This is baseless. While it is true that you need to be an excellent candidate, do not think that excellence can only be achieved in international events. Get good grades, get good test scores, make the best use of the resources available, be honest and sincere in whatever you do, and hope for the best.

Should we send only SSC/HSC/O-levels/A-level results, or do we need to send transcripts of internal exams?

-You’ll hear different opinions on this one, but it depends on whether the internal exam results will hurt or help you. If you never took the school exams seriously (a lot of people don’t) but got all A’s in your O-level/A in your SSC, make sure to distinguish the admissions office by sending abysmal grades that do not reflect your true capability. On the other hand, if your school grades are consistent with or better than your external grades, sending them is a good idea: They can only boost your chances.

A couple of notes: First, some schools need to give you a choice about whether you can send your school grades or not. I was at Notre Dame College, and the school transcript was included with the guidance counselor’s recommendation; it took a lot of work to opt-out. In that case, the best you can do is add a note explaining why the school exams do not show your true strength. Second, if you want to apply before your A-levels/HSC are over (which you have to do if you don’t want to take a gap year), it would be best if you had “predicted grades” from school and predicted grades usually need grades of some actual exams with it, in this case, which would be grades of internal exams.

To sum up: First, see if you have a choice. If you do, then do whatever makes your application stronger.

What do you mean by “Class of 2015”?

In the U.S., it is customary to call a class by the year they graduate and leave university, not by the year they enter university. This is different from the custom in your country, where a type (more commonly known as “batch”) is called by the year they enter. So, the type or batch that entered BUET last year is called Batch 2011 or Class of 2011, but the batch that entered MIT the previous year is known as the Class of 2015 since it usually takes four years to graduate, and most of the students will graduate in April 2015.

FAQs about recommendation letters

Who will you write the recommendation letters?

Teachers who know the applicant well and teachers whom the applicant knows well.

How many letters should I send?

Schools ask for three letters- one from the ‘guidance counselor,’ one from a science teacher and one from a humanities teacher. You can request more recommendation letters as well. But remember, do that only if the extra recommendation letter adds significant information to what others say about you. For example, my IMO coach knew me much better than my school teachers, so I got an extra letter from him.

Who is a ‘guidance counselor’?

You can designate any teacher of your choice to be your guidance counselor if your school has no particular assignment. However, in some cases, schools assign a specific teacher to be your ‘guidance counselor.’

What should be on the letters?

For teachers

Qualities that make the student unique. Suppose you talk about something other than how the student gets all As in their school work. The Admission Committee can see that from his/ her transcripts. Tell the Ad Com how the student is good at understanding poetry, for example, or how the student comes up with beautiful interpretations of numbers/ physics equations. Tell stories- Maybe once the student impressed you by proposing a novel chemical production; maybe they solved a problem after trying persistently for days; perhaps they wrote an excellent article that touched your heart. Talk about incidents that demonstrate the student’s presence of mind, perseverance, and passion.

Focus on the student’s humane qualities as well. Again, tell the Ad Com life stories. The student once helped a peer who became sick in the middle of an exam, or they ran a free school for local kids, and how they never gave up despite struggling with family problems. If the student is helpful, open-minded, and diligent if they do not give up easily, if they can get up after failing once, twice, or even several times, if they do even tiny things to improve the lives of other people, let the Ad Com know!

For students

Compile a list of anecdotes that demonstrate the qualities mentioned above and whatever you want your teachers to address in your recommendation letters. Meet with the teachers several times and talk to them about what you want them to write. Please give them the information packet two/to three months before the due date. Tell them about the postmark deadline and keep reminding them.

How should I send in the recommendation letters?

Some universities allow their applicants to submit recommendation letters online. In that case, give your teachers the URL of the posting site. If you decide to mail them, share your teachers’ envelopes and the addresses of the schools’ admission offices. They can use your high school’s seal on the envelopes if they want. It is not required.

You can send in your recommendation letters for your teachers as well. In that case, collect SEALED envelopes containing your recommendation letters from your teachers. Put the SEALED envelopes in a bigger envelope and send them in.

Remember, if you are sending in your recommendation letters, it is essential that the envelopes containing the letters are absolutely sealed.

What carrier should be used for sending recommendation letters?

-Personally, I prefer DHL (2000 taka/ package). Your letters will be in safe hands, and you don’t have to worry about them getting lost. But DHL is expensive. In that case, you can use the EMS service of the Bangladesh Post office (to 700/package). However, it might take a long time for the package to arrive if you use EMS. So post them early. There is a better way if you have relatives/acquaintances in the U.S. You can put all your envelopes in a big package and send them to your relatives. Then they can post them using the U.S. Postal service. It is a much cheaper and safer way to deal with your package. However, remember that if any university does not receive your package; they will send you emails reminding you to send those materials.

Things to be careful about

Plagiarizing (even copying a few sentences) from online recommendation letter samples or recommendation, letters of previous applicants will tell upon your Admission. The admission committee has ways of detecting these things. Trust us. You and your teachers should be careful about that.

SAT: General FAQ for university admission process

1. What is the SAT?

Read this: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SAT

You can also buy any SAT Preparatory Book and read the first few pages.

2. What is SAT II or the SAT Subject Test?

Wikipedia to the rescue again: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SAT_Subject_Tests

3. How vital is SAT? How much is it weighed in the university admission process?

It depends. If you have an otherwise powerful application, you can feel less queasy about your just-about-okay SAT score. If the rest of your application is just-about-okay, you better ensure your SAT score is flashy enough to draw attention. It also depends on what sort of university you are applying to. No SAT score can impress Harvard and Stanford – they have a few hundred perfect scorers applying yearly. (That does not mean a poor score cannot get you rejected.) On the contrary, a near-perfect SAT score will almost certainly get you into Purdue University or the University of Texas at Austin. Although these are both outstanding universities (for the record, Sheldon Cooper did his bachelor’s at UT Austin), their class size is several times bigger, and they don’t have 100 valedictorians fighting for every spot.

4. How many words should I memorize for the English part of the test?

Let me clear a grave misconception: SAT IS NOT AN ENGLISH TEST. Your success on SAT does NOT depend on how well you can memorize that atrocious list of 3500 words in Barron’s. SAT is designed to be a reasoning, aptitude, and intelligence test that predicts how well you can learn new concepts. The only problem is that since the test is in English, it puts people whose first language is not English at a severe disadvantage. How can you critically analyze an article if you need help understanding half of it?

SAT tends to use reasonably advanced English words, and high school students in Bangladesh, especially the ones in Bengali Medium who learned English from our glorious English for Today book, have a challenging time understanding the articles. This is how the myth of memorizing words started off.

Realizing that they don’t understand most of the tests, students in Bangladesh and many non-English-speaking countries thought that if only they knew the meaning of every word, they could get a perfect score.

I stress again that SAT is a reasoning test, and critically evaluating an article and understanding the meaning of every sentence is two entirely different things. You will make far more mistakes in your test just because you reasoned incorrectly rather than because you needed to understand the meaning of something. But does that mean you don’t need to learn new words? Of course not.

You will need to learn unfamiliar words, but a) don’t make memorizing words your priority, and b) does not set out to memorize a 3500-word list. If you want to memorize something, the best thing to learn would be the direct hits word list uploaded in the group. Then, try remembering the Hit Parade in The Princeton Review book and the hot prospect and high-frequency words in Barron’s. Taking overlaps into account, you should know about 800-900 words to get a decent score on SAT.

Unfortunately, If you aim for a near-perfect score, you will need to learn more words. Memorizing a long word list is not the best approach to vocabulary (Come on, man, it’s boring and uncool!). Still, if you’re exceptionally good at tedious memorization and enjoy tormenting yourself, you can do it.

5. Any advice for the Math Section?

With enough practice, Math is the easiest to score high. Take some practice tests and see where you have weaknesses. Then pick up any decent SAT prep book (Barron’s/Princeton Review/Gruber’s/Kaplan), learn those concepts and do a lot of practice questions.

If you are confident about your Math skills, it’s possible to get a perfect 800 in Math for you. It would be best if you practiced the art and craft of solving tons of easy problems fast and correctly. The Math section of SAT is often curved very harshly – just one mistake can sometimes drop your score by 40 points to 760. This will be gruellingly tedious, but if you practice 10 Math sections (with about 20 questions per section, that’s about 200 questions) the last 3 days before your exam, your chance of getting a perfect score will be significantly higher. You will also learn to notice the silly little errors you make, and in the actual exam, you will be able to spot those errors more quickly and correct them.

6. How should I prepare for SAT Subject Tests (SAT II)?

Both HSC and A-level syllabi are excellent preparation for Mathematics, Physics, and Chemistry Subject Tests. In addition, you should get yourself at least one standard SAT prep book like Barron’s or Princeton Review to supplement your studies and ensure you get everything just because it wasn’t in your school syllabus.

In my experience, the Princeton Review books have the same difficulty level as the actual tests, and Barron’s books tend to be slightly more complicated. But both should prepare you well enough for the test. As for the Biology Subject Test, the HSC Textbooks could be more helpful. We suggest you look at the A-level textbooks and use one or two prep books.

I Refrain from speaking for the other subject tests. Try to find people who have taken them in the past, look through some prep books, and take some practice tests.

7. Where do I find the books?

Most of the SAT preparatory books (College Board Official SAT Study Guide/Barron’s/The Princeton Review/Gruber’s/Kaplan/McGraw-Hill – you name it) can be found in bookstores or online markets. If you look online, you can get pdf copies of a lot of books, but it’s illegal for us to post the links here; you have to find them yourselves.

8. How do I register for the SAT?

You can go to the SAT website (sat.collegeboard.org) and register there. You will need an international credit card to pay the fees. If you do not want to use a credit card, you can get a paper registration form from American Center and register by mailing the form and a bank draft to the USA. Please visit the American Center in person if you’re interested, and they will let you know the details.

If you are planning to go abroad, you’ll soon be Paying lots of different fees for different purposes. I recommend you arrange with one of your relatives or friends or friends of parents living abroad to Use their international credit card to pay these fees before you start the university admission process. Your life will be so much more straightforward, and you will save a lot of money by not having to mail bank drafts to North America every time.